Quilt making fulfils a number of roles for the maker and society: the process of making may represent an act of remembrance, a rite of passage (say a wedding or a birth) or provide a forum for overt political or social commentary.1 Stitching may be a solitary occupation, a moment to reflect or meditate, or a communal activity, as illustrated by the evocative image of the quilting bee.2 The beautifully crafted quilts produced either in isolation or in communities form part of a cultural continuum that transcends time and place; their makers creating both ‘personal and historical legacies’.3

The process of making can also be a challenge, forcing the maker to admit and face up to stark truths and harsh realities, particularly those associated with the untimely or tragic death of a loved one. In this case, the creation of a tangible memorial to a lost family member or friend provides succour in the aftermath of a personal tragedy; the physical act of stitching also acts as a lynchpin on the therapeutic road to emotional recovery. Cloth, with its complex and fascinating history, has long been acknowledged as playing a key role in retaining and communicating both personal and communal memories, those complex narratives which make up our own and our ancestral lives. Kathryn Sullivan Kruger believes that ‘[A] piece of fabric transmits information about the society which created it in a manner not dissimilar to a written language, except that in this case the grammar is printed in the cloth’s fibre, pattern, dye and method of production.’4 The monumental ‘AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and ‘National Tribute Quilt: A September 11 Memorial’ both reflect the collective efforts of individuals and communities to come to terms with tragic and untimely loss, focusing on specific events in recent history. These objects, with their intimate associations of warmth, comfort and the security of home therefore become public metaphors in times of national and international tragedy and instability.

Collective Memories

Initially organised at a local level in the mid-1980s, ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ has since evolved into an international project. The extraordinary number of individually stitched panels commemorates the thousands of men, women and children who have died of the disease since 1985.5 Colleagues, friends, families and lovers have all contributed to what has become known as the world’s largest living memorial. Unlike most collective monuments to the dead, the majority of which consist of seemingly impersonal lists of names and dates incised into stone or marble, ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ is unique in celebrating the individuality of the people who have died. Personal tokens, mementoes and memories are crafted into many of the panels. When the panels are assembled the quilt functions not only as a conduit for the grief and anger of those who have lost a loved one, but also as a celebration of a life lived.

In a unique chapter in the formation of the quilt, fashion designer Rifat Ozbek approached key individuals in the fashion industry to design panels dedicated to colleagues whose deaths had decimated the creative industries. A small publication documents and illustrates a selection of these panels,6 including some of the written tributes. These poignant and, in some cases, intensely personal dedications, reinforce the power of the medium to bear witness to both individual and universal suffering. Ben de Lisi focused on the loss of a ‘silver-haired man [who] was a true friend under all circumstances … [who] nurtured and nourished us … To say we loved him would be an understatement. To say we needed him would be obvious. To say we miss him … we will always miss him.’7 Helen Storey directed her anger at the unfairness of the disease, at ‘the painful passivity displayed on the faces of children for whom life is defined by disease … A seemingly godless earth to allow a being unable to shape its own destiny.’8 Exhibited on both sides of the Atlantic, the quilt is also used as an educational tool: as the rate of HIV infection among young people continues to rise, the significance of ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ continues to resonate, telling ‘a story significant to the time in which it was created’.9

‘The National Tribute Quilt’ : A September 11 Memorial (2002)

‘The National Tribute Quilt’, like ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’, functions both as a personal commemoration and as a symbol of national unity. Initiated by the Steel Quilters in Pittsburgh,10 the 3 metre × 10 metre quilt includes the name of every individual who lost their life in the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. Designed as a series of six panels, it has four central panels based on an image of the New York City skyline, complete with the twin towers of the World Trade Center. The central section of the quilt is flanked on the left by a panel which includes the names of passengers and crew who lost their lives on Flights 11, 93, 175 and 77, surmounted by a pair of white doves. The right hand panel commemorates individuals who died at the Pentagon. This panel is dominated by the profile of the head of an eagle, a symbolic metaphor for both the Pentagon and the USA.

The Steel Quilters, a group of four experienced quilters and stitchers, were moved to construct a lasting memorial to the dead while watching media coverage of the tragedy. Kathy Crawford describes being moved by the composure of a co-worker’s family whose son had died on his first day working in the World Trade Center; 'The father’s strength and composure inspired us to make this quilt, not just for one family, but for all the families who must share in the grief. A quilt which would not only serve as a way to forever remember and pay tribute to those lost, but also give comfort to their families knowing that others truly cared about their loved ones.11 The Steel Quilters extended their project to the wider community via a website that invited individuals interested in contributing a square to contact them for the name of a victim. Kathy Crawford provides an explanation for the overwhelming response to the project: ‘Many block contributors researched the person to whom they were paying tribute. Many cried while making their blocks, feeling close to someone that they had never met but with whom now they have a bond. Many wrote mails and letters accompanying their blocs, expressing their gratefulness for this project for helping them to get through emotions which many of us have never experienced before.’12 The complexity of creating a memorial which contains 3466 squares was offset by a grid reference system that enables each name to be located on the quilt and in the accompanying record book (the book also contains the square-maker’s name).

Central to the act of remembrance through the creation of memorials is the ability to record the name of the deceased. The unprecedented nature of the tragedy of 9/11added an unforeseen complexity to the creation of ‘The National Tribute Quilt’. The Steel Quilters used the list of victims provided by the media giant CNN as the basis for their website appeal. As the list of names was constantly being revised and updated, the task became increasingly complicated. The Steel Quilters’ decision to add a disclaimer to the website appeal was both pragmatic and practical – the quilt had gone through a process of modification, as names were removed or spellings amended, and squares were removed or altered to reflect the change. The importance of ensuring that the memory of each individual is correctly recorded is central to the act of remembrance – failure to do this would invalidate both memorial and, metaphorically, the individual.

The success and level of response to the ‘The National Tribute Quilt’ owes much to the way in which the American quilting tradition is firmly entrenched in the nation’s psyche. For many, quilt making is synonymous with the creation of a national identity; it represents the pioneering spirit of the early settlers on their arduous journey west, the mythology of ‘The Underground Railroad’ quilts**13** and the sense of community personified by the nineteenth-century quilting ‘bees’.14 On continuous display at the American Folk Art Museum, New York, the quilt represents both personal and collective memories.

‘Memoriam’ – A Personal Testament (2002)

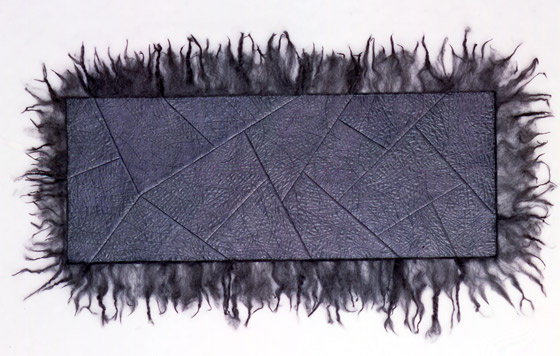

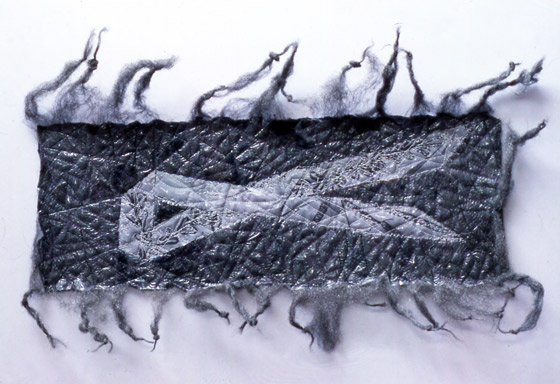

Community projects such as ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and ‘The National Tribute Quilt’ fulfil a specific function in society – a catalyst for emotion and commemoration. When community projects focus on major events with international repercussions, the resulting quilts are recognised and classified as cultural icons. In contrast, Michele Walker’s ‘In Memoriam’, a plastic and wire wool quilt, is more difficult to read. Dedicated to her mother, Walker’s referencing of the distressing symptoms experienced by individuals suffering from Alzheimer’s disease is a complex combination of personal narrative, social commentary and traditional quilt making skills.

Trained as a graphic designer, Walker’s two publications celebrate both the unknown makers of traditional North Country quilts and the work of contemporary practitioners.15 Walker, one of a small group of contemporary artists who revived interest in British quilt making in the 1970s and early 1980s,16 continues to create complex and multi-layered quilts and installations. Lesley Millar, curator of the cross-cultural exhibition ‘Cloth and Culture Now’, believes that many practitioners who consciously draw on indigenous textile traditions use ‘the cultural space presented by the domestic history of the making and use of textiles, to move between [both] the personal and the political’.17

‘Memoriam’ is the last quilt in a body of work which draws inspiration from the patterns, stitches and ethos of traditional quilt making – the incorporation of everyday, cast-off scraps and fabrics used to make both decorative and functional bed covers. Walker’s ability to both understand and interpret the origins and traditions of this craft provides her with a medium with which to engage with social, political and environment issues in a way which is both accessible and relevant. Walker states, ‘My work deals with re-interpreting the traditional quilt. Inspiration comes from what I experience and observe around me. It is essential that the content of the work reflects the time in which it is made … I aim in my work to challenge the associations and meaning of the word quilt.’18 An earlier work, ‘Waste Not, Want Not’ (1993),19 thus not only engages the viewer in the topical debate regarding recycling, but also references the ‘make do and mend’ tradition of crafting objects from the ephemera of our everyday lives. Constructed from frozen food packaging, plastic bags, fabric and photocopies, ‘Waste Not, Want Not’ is both an emotional and intellectual response to the environmental issues which continue to resonate across the globe. In ‘Assault and Battery 3’ (2001),20 Walker again combines her knowledge of the North Country quilt making tradition with direct criticism of battery farming. Made in response to a report published by Compassion in World Farming,21 ‘Assault and Battery 3’ is a rectangular quilt constructed from plastic materials, wadding, Vilene and feathers. It is the third in a series of quilts based on factory farming. The imagery, a pair of large white feathers against a black rectangular background, references the ‘running feather’ quilting pattern used in traditional North Country whole-cloth quilts. The aesthetic reading of the quilt is subverted by the title – an overt commentary on the conditions related to factory farmed poultry, especially turkey rearing.

Walker’s interest in traditional British patchwork and quilting extends beyond materials and techniques. Underpinning her research is her fascination with the lives of the often unknown working class women who produced whole-cloth quilts, objects which are, on the whole, unsigned and undated but retain the fading memory of traditional folk crafts of rural and mining communities. Walker’s concern is well founded: the seminal 1971 exhibition ‘Abstract Art in American Quilts’ held at the Whitney Museum of Modern Art in New York may have catapulted the crafted object into the fine art arena, yet the makers remained conspicuously absent.22 In contrast, the phenomenal success of the Gees Bend quilts is as much a response to the social history and documentation project, and the ability to trace the lineage of the makers, as it is to the aesthetic quality of the work.23

It is this emphasis on ‘disappearance’ – both physical and metaphorical – that underpins Walker’s ‘Memoriam’. On the surface, the work can be read in terms of a commemoration of the erosion of traditional skills and the identities of the women who practiced them. Dedicated to her dead mother, ‘Memoriam’ is firmly rooted in the tradition of commemorative quilts, yet its underlying focus is as much on the loss of an individual’s memory as it is on remembrance. Walker’s intensely personal yet deeply complex exploration of the distressing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease can in many ways be compared with the origins of ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ – anger at an apparent lack of support for sufferers from Government agencies and a desire to increase awareness of the disease.

A progressive and fatal brain disease, Alzheimer’s destroys brain cells, resulting in serious memory loss, deterioration in thinking and concentration, and severe behavioural problems, and is the most common form of dementia. In discussing ‘Memoriam’, Walker describes how her mother developed dementia and eventually lost both her memory and her sense of identity, a process which is translated into the stitching of the quilt. The sculptural quality of the stitched layers of clear plastic over the metallic grey of the wire wool acquires a more macabre subtext when it is revealed that the design is based on the pattern of Walker’s own skin. Traditionally, quilt makers would use inanimate objects as aids in drawing patterns to be stitched – the plates, cups, even chair seats which were readily available in every home.24 Walker has replicated this process, drawing attention to the transitory nature of the life itself by using her own, animate body as a template, creating a surface pattern at once aesthetically intriguing and emotionally unsettling. Equally, the incorporation of wire wool into the work functions as both material (traditional whole-cloth quilts use wool or cotton as wadding) and as a metaphor for decay – the wire wool gradually reacts to exposure to the atmosphere and in time decays. Here Walker draws again on her knowledge of quilting techniques, piecing each section of the quilt in the manner of a late nineteenth-century ‘crazy’ quilt;25 an ironic reference to the continuing trend to ‘institutionalise’ or hide the mentally ill, a reference which is reinforced by the use of the industrial grey wire wool, a colour most often associated with hospitals or asylums. Walker’s powers of observation are both acute and disturbing. She describes the meaning behind the twisted and knotted wire wool borders of the quilt, ‘As my mother lost her memory she became obsessive about everyday things, small things that didn’t really matter; she would sit and twist and tease her hair. I noticed that many of us obsessively twist our hair without realising, particularly when lost in thought’.26 This laying bare of an intensely personal narrative, in a medium that is both familiar yet abstract is, in Jane Jakeman’s view, ‘sometimes uncomfortably negotiated into public space’.27 Yet Walker’s exploration of the self, both in terms of recreating through stitch the patterns of her skin, and referencing the absence of her mother, both physically and metaphorically through the loss of her identity, create an evocative continuum with the unknown makers of the past.28 The quilt, so often associated with gift giving and traditionally handed down as an heirloom through the female line, and a symbol of familial female heritage, becomes a highly charged and complex study of the relationship between mother and daughter. Walker states ‘The “emptiness” of the quilt evokes the void I felt during those years. Working with an uncomfortable tactical material like wire wool seemed to be symbolic of those bittersweet memories. The work was made several years after my mother’s death (in 1998); I needed that period of time to distance myself from what had happened and have a period of reflection.’29

In the study accompanying ‘In Memoriam’, Walker has included a piece of her mother’s wedding veil, looped and stitched to reference the universal remembrance ribbons that started with AIDS awareness. The red ribbon, traditionally worn on World AIDS Day and throughout the year to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS, has been adopted by a number of charities – the meaning behind each ribbon dependent on its colour or colours.30 The ribbon has also become a symbol of American unity, replicated in the pattern of the American flag and the strapline ‘Support Freedom’. Walker has explored the significance of the awareness ribbon in an earlier work ‘Remember Me’ (1999).31 However, in this context the use of a personal memento is again symbolic of Walker’s ability to move beyond the obvious. Juxtaposed with ‘Memoriam’, the study is a poignant reminder of both the hopes and fears of a young bride at the start of her new life. As our mothers hand down these physical heirlooms, so too do they hand down our histories in the form of stories and narratives that help to cement our sense of identity. The inability to recall those narratives, the loss of our own histories, challenges the enduring importance of the mother/daughterrelationship and begs the question ‘Who am I, where do I come from’?

‘Memoriam’ has most recently been included in ‘The Fabric of Myth’ exhibition held at Compton Verney. Antonia Harrison, co-curator of the exhibition, agrees that Walker’s use of unconventional materials challenges our perceptions of the quilt, its ability to evoke memories of warmth and security and our poignant recollections of mothers kissing us goodnight. Yet the scale of ‘Memoriam’, unlike the monumental ‘AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and ‘The National Tribute Quilt’, recalls the domestic and the intimate, as does Walker’s decision to display the quilt horizontally, a reference to the quilt’s traditional function as bed cover. Walker is adamant that the quilt should be placed on a high plinth, creating the impression of a medieval effigy or the tombs of the great and the good, whose names are forever immortalised in stone and marble. This analogy is again heightened by Walker’s use of materials, the exclusion of soft feminine fabrics, chintz and florals, in favour of ‘hard’ plastic and wire wool. Harrison echoes this comparison, ‘The quilt that would normally be passed down through generations retaining memory has instead become a shrine to its loss’.32

‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and ‘The National Tribute Quilt’ bring private grief and anger to a very public forum. Although criticised by some as overly sentimental,33 the quilts provide a focus for both commemoration and campaigning. ‘Memoriam’ is, first and foremost, a work of art: its meaning complex and multi-layered. Yet it also commemorates a very private relationship and personal loss. Walker believes that her interest in memory and identity, both personal and collective, emerged through the experience of ageing. ‘With the loss of parents you start to question things, to witness my mother’s mental decline was a terrible event but in a way it gave me a new insight. I had taken memory and therefore a sense of identity always for granted, but when you are close to someone who has lost their memory and connection with you as their daughter – well, that sense of loss takes on a different relevance’.34

Endnotes

-

‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and ‘The National Tribute Quilt’ are two more recent examples of community-led ‘protest’ quilts. However, the tradition of stitching quilts which would fulfil both the social and spiritual needs of communities is firmly rooted in the scripture and signature quilts of the nineteenth century. For a discussion of the importance of scripture and signature quilts see Allan, Rosemary. ‘Chapel and Signature Quilts’. Quilts & Coverlets: The Beamish Collections. County Durham, 2007: 81–87. See also ‘Quilts Bearing Names and Other Writing’. Quilt Treasures: The Quilters’ Guild Heritage Search. London, 1995. The V&A has one scripture quilt in the collection (V&A museum no. T.67-1970). ↩︎

-

See, for example, Ralph Headley’s oil painting ‘The Wedding Quilt’ (1883) (Private Collection) reproduced in Osler, Dorothy. North Country Quilts: Legend and Living Tradition. County Durham, 2000: 25 and Allan, Rosemary. ‘Chapel and Signature Quilts’. Quilts & Coverlets: The Beamish Collections. County Durham, 2007: 90. ↩︎

-

See Stalp, Marybeth C. Quilting: The Fabric of Everyday Life. Berg, 2007: 43. In this publication, Stalp, a sociologist and quilter, writes a contemporary commentary on the reasons that women quilt, including an exploration of personal identity issues such as marriage, childcare, friendship and the ageing process. ↩︎

-

See Kruger, Kathryn Sullivan. 'Clues and Cloth: Seeking Ourselves in ‘The Fabric of Myth’. The Fabric of Myth. Compton Verney, 2008: 11. Written to accompany an exhibition of the same name held at Compton Verney 21 June – 7 September 2008. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt’ and a comparison with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington see: Hawkins, Peter S. ‘The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt’. Critical Inquiry 19:4 (Summer, 1993): 752–79. ↩︎

-

Always Remember. A Selection of Panels Created By and For International Fashion Designers. New York, 1996. ↩︎

-

Always Remember. A Selection of Panels Created By and For International Fashion Designer*. New York, 1996: 28. ↩︎

-

Always Remember. A Selection of Panels Created By and For International Fashion Designers. New York, 1996:108. ↩︎

-

See Kruger, Kathryn Sullivan. 'Clues and Cloth: Seeking Ourselves in ‘The Fabric of Myth’. The Fabric of Myth. Compton Verney, 2008: 11. ↩︎

-

‘The Steel Quilters’ consists of a small group of quilters who work for the United States Steel Research and Technology Center. Based in Monroeville, near Pittsburgh PA, the four women co-ordinated the nationwide project. It took 12 volunteers (all women) two days to lay out the 3466 squares on a grid. It took 250 hours to stitch the quilt together. ↩︎

-

Kathy Crawford National Tribute Quilt Dedication Speech, July 8, 2002. ↩︎

-

Kathy Crawford National Tribute Quilt Dedication Speech, July 8, 2002. ↩︎

-

The question of whether quilts were used to assist enslaved men and women on their journey to freedom has divided academics. For more information see Tobin Jacqueline L. and Raymond G. Dobard. Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad. New York, 2000 and Brackman, Barbara. Facts and Fabrications: Unravelling the History of Quilts & Slavery. California, 2006. ↩︎

-

Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock discuss the role of the quilt in American society in ‘Craft Women and the Hierarchy of the Arts’, in particular the role of the quilting bee in the local community in Parker Rozsika and Griselda Pollock. Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology. London, 1981: 50–81. ↩︎

-

See Walker, Michele. The Complete Book of Quiltmaking. London, 1985 and Walker, Michele. The Passionate Quilter. London, 1990. ↩︎

-

Walker, together with Jo Budd, Pauline Burbridge and Dinah Prentice exhibited in one of the first pioneering exhibitions to change the perception of British quiltmaking in Take 4 – New Perspectives on the British Art Quilt. The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, September 1998. ↩︎

-

Millar, Lesley. ‘Transition and Influence’. Cloth & Culture Now. Surrey, 2008: 7. ↩︎

-

Walker, Michele. Personal statement Crafts Council Listing. Accessed 1 September 2008. http://www.photostore.org.uk ↩︎

-

‘Waste Not, Want Not’ is in the collection of the Sunderland Museum and Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear. ↩︎

-

‘Assault & Battery 3’, in the collection of the Shipley Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear. ↩︎

-

See Steveson, Peter. ‘The Welfare of Turkeys at Slaughter’. A Report for Compassion in World Farming Trust, December 1997. Accessed 1 September 2008 ↩︎

-

Parker and Pollock discuss the Whitney exhibition in ‘Crafty Women and the Hierarchy of the Arts’, p.71. Interestingly, Jonathan Holstein entitles his publication Abstract Design in American Quilts: A Biography of an Exhibition. University of Nabraska, 2002 (my emphasis), a title which further serves to distance the maker from both object and public forum. ↩︎

-

There are a number of publications documenting the Gee’s Bend quilts and covers. See John Beardsley et al. Gee’s Bend: The Women and Their Quilts. Atlanta, 2002. For a critique of the Gee’s Bend exhibitions in relation to cultural politics see Chave, Anna C. ‘Dis/Cover/ingthe Quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama’. The Journal of Modern Craft 1:2 (July 2008): 221–54. ↩︎

-

Rosemary Allan discusses designs on whole-cloth quilts in Allan, Rosemary. ‘Chapel and Signature Quilts’. Quilts & Coverlets: The Beamish Collections. County Durham, 2007: 99–105. See also Walker, Michele. The Passionate Quilter. London, 1990: 10–21. The V&A has several whole-cloth quilts in the collection (V&A museum no.T.133-1932 (South Wales) and V&A museum no.T134-1932 (County Durham)). ↩︎

-

The vogue for ‘crazy patchwork’; the elaborate and colourful combination of silks, satins and velvets swept the UK, America and Australia. Although considered by some to be garish and in poor taste, contemporary reports hailed it as both fashionable and versatile, being equally suitable for piano covers, antimacassars, sofa pillows and table covers. Often embellished with an accomplished range of embroidery stitches, these cushions and tea cosies provide evidence of the vibrant dress fashions of the period. The V&A has one crazy patchwork table cover in the collection (V&A museum no.T.682-1994). ↩︎

-

Michele Walker in conversation with the author, 30 August 2007. ↩︎

-

Jakeman, Jane. ‘Soft Architecture. A review of The Fabric of Myth Exhibition’. Times Literary Supplement, 4 July 2008. ↩︎

-

In 2000 Walker visited Japan in conjunction with an exhibition about contemporary British quilted textiles. Here she discovered sashiko and became interested in the indigo-dyed garments used for work clothes. A three-year AHRC Fellowship enabled Walker to research sashiko textiles and women who made them. Walker states, ‘Similar to those who made quilts in Britain; the majority of these Japanese women lived in working class communities and were considered ordinary and unimportant. Their lives centred on survival. My research into personal histories has only been made possible through friendships that have gradually evolved with a few women who are now in their late eighties or nineties and to whom sashiko is still remembered as being significant in their lives’. (In conversation with the author 30 August 2007). Walker’s research culminated in two exhibitions: ‘Memory Sticks’, Fabrica, Brighton Festival, May 2005, and ‘Stitching for Survival’ University Gallery, Brighton, October 2007. A full transcript of the Author’s interview with Walker by the author accompanied this exhibition. ↩︎

-

Michele Walker in conversation with the author, 30 August 2007. ↩︎

-

The purple ribbon used by Alzheimer’s disease campaigners has also been adopted by domestic violence awareness, childhood stroke awareness, and pancreatic cancer awareness and to promote religious tolerance. ↩︎

-

‘Remember Me’ is in the Crafts Council Collection. ↩︎

-

Harrison, Antonia. ‘Weaving, unweaving and reweaving: the legacy of Penelope’. The Fabric of Myth. Compton Verney, 2008: 39. ↩︎

-

See Hawkins, Peter S. The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt. ↩︎

-

Michele Walker in conversation with the author, 30 August 2007. ↩︎