'Grand Polychromatist-plenipotentiary’ and perpetrator of bad taste,1 and, ‘the most learned man, perhaps in all Europe, in Eastern decoration’;2 Owen Jones gained both notoriety and fame in his day. Yet the sparsity of serious historical attention given to Jones is surprising, considering his role in the history of the decorative arts, design education, and the development of the South Kensington Museum, the continuing success of some of his designs (versions of his wallpaper designs marketed in the 20th century by Laura Ashley), and continuing sales of The Grammar of Ornament.3 The display and Study Day planned at the V&A by the Collections Department of Word and Image to commemorate the bicentenary of Jones’s birth in 2009 will hopefully start to redress this absence.4

For a researcher, it is a delight, but perhaps not a surprise, to discover close links between objects in the V&A collections and the work of a figure so embedded in the foundation and philosophy of the Museum. My recent research has focused on the Museum’s nineteenth century Indian textile collections and this article will focus on apparently unobserved connections between these collections, Jones’s Grammar of Ornament, and his own designs.

Jones, Indian art, and the formation of the V&A collections

As a young architect, Owen Jones was profoundly influenced by his travels and observations in Egypt, Turkey and Spain (notably the Alhambra) in the 1830s. As Michael Snodin has commented, ‘His foreign experiences were to lead directly to a set of architectural and design theories which combined the pure romanticism of the East with a scientific approach to design, ornament and colour’.5 Some of these experiences were vicarious; he did not actually visit India, or indeed many of the countries whose art was represented in the pages of The Grammar of Ornament, first published in 1856. This was not, after all, the age of jet travel. Jones acknowledged in the Grammar that the section on Indian Ornament drew heavily on objects shown in the Exhibitions of 1851 (London) and 1855 (Paris).6 The Indian displays at these exhibitions were assembled via the East India Company and an elaborate network of committees and sub-committees in its four Presidencies in India: Bengal, Agra, Madras and Bombay, following an exhaustive classification system devised by the Exhibition Commissioners in London.7 Textiles and clothing accounted for seven of the twenty-nine classes of materials exhibited.

In ‘Gleanings from the Great Exhibition of 1851’, published in the Journal of Design, Jones reflected on the meretricious values of the European manufactures: ‘After wandering through the halls of this most wonderful assemblage of the world’s industry, the artist who passes down the nave from east to west will see on either side but a fruitless struggle to produce in art novelty without beauty – beauty without intelligence; all work without faith’.8

Jones considered that in comparison, ‘The Indian and Tunisian articles were the most perfect in design of any that appeared in the exhibition … a boon to the whole of Europe’.9 The Indian work in particular showed, ‘all the principles, all the unity, all the truth, for which we had looked elsewhere in vain’.10 In this he echoed a broader admiration of Indian artefacts, especially textiles, which had first come to the attention of a mass public at the 1851 Exhibition, and to that of a more limited audience at the East India Company’s Museum.11 Here was possible redemption from the ‘carpets worked with flowers whereon the foot would fear to tread’, and other horrors of contemporary industrial production.12

It may be useful to describe briefly the method by which Indian objects were brought into the South Kensington Museum following the 1851 exhibition, since Jones was critically involved in this. The broader context was summarised by Clive Wainwright who, although challenging the assumption that 1851 purchases defined the South Kensington Museum collections, admitted the key roles of Henry Cole, Richard Redgrave, and Owen Jones in their formation.13 These individuals, together with A.W. Pugin (whose demise occurred during the process) and John Rogers Herbert, formed the committee for selecting objects from the Great Exhibition for the School of Design collection displayed at Marlborough House that was to form a substantial core of the Museum. Time was short. Wainwright has drawn attention to the following entry in Cole’s Diary for 8 October 1851: ‘Redgrave, O. Jones met and examined French and Indian articles for Schools of Design.’ This was done in the exhibition itself, starting at seven o’clock in the morning, before the admission of the public. The following day’s entry noted, ‘Completed examination of Articles except Indian. Too numerous in good things.’ Wainwright noted that nearly a quarter of the £5000 budget allocated by the Government was eventually spent on Indian objects from the exhibition, and of these Indian textiles were very well represented, accounting for sixty-five out of the 139 items purchased from the display.

A further £500 was spent the following year at the East India Company auction of Indian objects that had failed to sell at the exhibition, although the Times commented that:

‘The collection comes before the public in a rather depreciated state, and with its chief ornaments abstracted … The Queen had the best of everything contained in it. The Government Commission made a careful and judicious selection for its Museum of Practical Art … many rare and valuable contributions were merely lent for the occasion of the Exhibition, and have been restored to their owners. The Company, too, have not been unmindful of their public duties have behaved most liberally to learned institutions and to scientific men’.14

These remaining objects could have been bought at knockdown prices, for as the Times noted, ‘Yesterday’s sale … realized … £800, most of the things going very cheaply, and some (especially the gold and silver tissues) being disposed of at great sacrifice’. The kincobs (silk fabric with patterns woven in a weft thread of gold and silver- wrapped thread), which had been so greatly admired,

… fared ill under the rude test of the auctioneer’s hammer, the prices they fetched [were] based upon the amount of precious metal used in the decoration. Though our greatest authorities in art manufactures have concurred in pointing them out as masterpieces of taste and skill, they have been bought as useless for any other purpose than what they may bring in the melting pot.'.15

Fortunately, a substantial number of superb kincobs and other woven silks remain in the V&A collections and more were bought in India in the early 1880s.

The Grammar of Ornament and the circulation of Indian art

Although Jones trained as an architect, his surviving reputation has been as a designer and decorator, a maker of books and as an educator. In keeping with the utilitarian and educational motives of Cole, the ‘Thirty seven Propositions’, or ‘General Principals’ set out by Jones in the Grammar had as their goal the general improvement of artistic standards through mass education. ‘No improvement can take place in the Arts of the present generation until all classes, Artists, Manufacturers and the Public, are better educated in Art’, he stated.16 The underlying idea was that the principles governing the use of design and ornament could be extracted and applied to manufactured objects that would be readily bought by similarly educated consumers. The intention of the Grammar was also that examples of pattern could be extracted from their context, absorbed by the viewer and appropriately reworked or applied to new manufactures, although direct copying was to be avoided.

Exemplary patterns were found by Jones principally in non-European decorative arts. In the words of the contemporary curator J.C. Robinson, ‘the contribution to the Exhibition of 1851 from various oriental countries were … recognised as possessing special claims to the attention of the decorative artist, and their superiority, in point of design, over European stuffs, was … for the first time, fully admitted’.17 At the 1851 Exhibition, ‘amid the general disorder everywhere apparent in the application of art to manufactures’, Jones found that Indian artefacts stood out in terms of their ‘unity of design … skill and judgment in … application’ and, ‘elegance and refinement in … execution’.18 Jones particularly admired the ‘equal distribution of the surface ornament over the ground’ and the use of, ‘the most brilliant colours perfectly harmonised’.19 Such themes became the leitmotif of the ‘good taste’ promoted by the South Kensington authorities.20

Jones intended the Grammar to reach as wide an audience as possible, particularly in the manufacturing districts of England, and, despite its cost, fifty copies of the Grammar and twenty-five copies of Jones’s Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (Owen Jones and Jules Goury, 1842–45) were purchased for distribution to Schools of Art in 1857.21 Thus details of Moorish, Indian, Chinese, Egyptian and many other types of designs could be inspected beyond the exhibition spaces of the capital. In addition, actual objects could also be seen. The establishment of a system of circulating exhibitions in the 1850s allowed for first-hand examination of a wide range of objects. Thirteen of the twenty-one textiles selected for circulation to museums and provincial schools of art in the mid-1850s were from India. Some schools also bought their own examples of Indian textiles, originally shown in the 1851 Exhibition; eleven pieces were bought for the Cambridge School of Art in the 1860s.22

The plates depicting ‘Indian Ornament’ in the Grammar were taken from ‘works in metal’, ‘specimens of painted lacquer work’ (from the East India Company collections) and ‘embroidered and woven fabrics’ shown in 1851 and at the Paris International Exposition of 1855. The sources of ‘Hindoo Ornament’ illustrated in Chapter Thirteen however, were architectural, and largely based on museum collections in London, copies of the Ajanta cave paintings, and Ram Raz’s History of the Architecture of the Hindus, published in 1834.23

The collections as source for the Grammar

During the course of recent research into the formation of the V&A’s Indian textile collections, it has been possible to identify a number of objects in the Asian collections which can be directly related to plates in the chapter on Indian Ornament in the Grammar. Although drawn by Jones’s pupils Albert Warren and Charles Aubert, and not by Jones himself, the objects were selected by him both for the museum collections and again for the book and deliberate exposure to a wide public. This gives a strong sense of historical continuity to objects in the collections and to Jones’s estimation of their aesthetic value.

As already noted, a feature of Indian decorative design particularly admired by Jones and his contemporaries was, ‘the equal distribution of the surface ornament over the grounds’.24 An example of this is a woven silk fabric with repeating flowering plant design from Aurangabad, now in Maharashtra (figure 1) which was illustrated in the Grammar (figure 2). It was purchased from the 1851 Exhibition for £4 and was also illustrated in Henry Hardy Cole’s 1874 Catalogue of the Indian collection at the South Kensington Museum as an example of good design on account of its muted colours, ‘flat’ design and regular repeat typical of the Mughal and Deccani style used in many media including textiles.

Indian Kincob were among the most sensational and admired fabrics shown in 1851 and at subsequent exhibitions. Kincob, an anglicised term of uncertain origin, is a rich silk fabric with patterns woven in a weft thread of gold and silver-wrapped thread (zari), made by wrapping gold or silver wire around a silk core (kalabuttu zari). Kincob was usually sold by weight. One example (figure 3) from Benares (Varanasi) has a gold ground and trellis design in silver, black and red, containing a flower pattern. It was purchased from the 1851 Exhibition for £32.10s (£32.50) and was described as ‘Kinkhob Jhaldar’ (Jhali or jali, trellis or net) in the 1852 Inventory and was illustrated in the Grammar (figure 4). The net or trellis pattern (jali) often referred to as a ‘diaper’ pattern, was a motif considered exemplary and emulated by design reformers such as Jones and William Morris.

Benares (Varanasi) was, and remains, famous for its silk weaving, and a number of examples from its workshops were shown at the 1851 Exhibition. A sumptuous sari (figure 5 , figure 5a) woven from crimson silk and gold-wrapped thread, was purchased from the 1851 Exhibition for £22. The patterned, loose end (pallu) of this of this sari incorporates flower motifs, a floral meander, chevron (khajuri) and floral designs and at least three of these motifs were illustrated by Jones in the Grammar (figure 6, figure 7, figure 8).

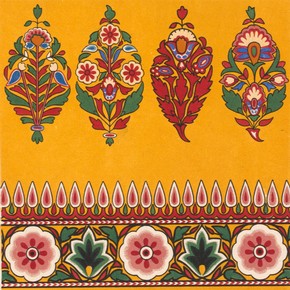

A variety of regional Indian textile techniques were shown in 1851, and at later exhibitions, Indian craft workers were brought to Europe to demonstrate their skills to the public. Indian embroidery was greatly admired in Britain in an era when embroidery was both practiced at home and promoted by the Arts and Crafts movement; a number of examples were represented in the Grammar. A motif taken from an embroidered Huqqa mat (figure 9), is illustrated in the Grammar (figure 10) Embroidered garments from Kutch (Gujurat) were purchased for the Museum from the 1851 exhibition, and at least two of these were illustrated in the Grammar: a curious black satin garment described as an ‘apron’ embroidered with designs of flowers and leaves (figure 11, figure 12, figure 12a) and part of an unsewn skirt made of yellow satin woven silk, embroidered in chain stitch with silk thread (figure 13, figure 14). Embroideries such as these were made by professional male embroiderers from the Mochi (shoemaker) community in Kutch for wealthy Indian patrons.

Other specialised techniques may have been unknown in Britain. Kota, in Rajasthan, which does not have a strong weaving tradition, was, and is still, famous for a fine translucent cotton cloth known as malmal, which imitates the more expensive gold silk brocade. The design is stamped in gum onto the fabric, usually muslin. A layer of gold or silver foil (either real gold or silver leaf or ground mica) is laid on top and rubbed in; the residue is then thoroughly beaten into the cloth so that it will resist wearing. A red muslin turban from Kota, overprinted in gold (figure15) was bought from the 1851 Exhibition for ten shillings (fifty pence); its lattice motif was illustrated in the Grammar (figure 16).

Jones’s designs and the Indian textile collections

Besides his architectural and educational work, Jones also practiced a wide range of applied design, including textiles and wallpaper. The influence of Indian textiles is apparent in several of Jones’s own designs, besides names such as ‘Nizam’, ‘Sultan’, ‘Peri’ and ‘Maharanee’ – all textile designs for Warner and probably named by the company.

Jones strongly discouraged the direct copying of the designs displayed in the Grammar, although he thought it was inevitable – a ‘dangerous’ and ‘unfortunate tendency of our time’, since it produced designs with no cultural context or meaning.25 Thus we would not expect Jones’s own designs to be mere copies, making it difficult to ‘match’ them exactly with their probable Indian sources. There are also problems in distinguishing between the many similar and common motifs of Indian textiles – used widely in other media including architectural decoration – such as the trailing vine, diaper or trellis, and various floral repeats, several of which were drawn for the Grammar, and also in ‘translating’ motifs from woven silks and embroidery to printed and woven patterns. In this respect, a woven silk from Aurangabad (V&A Museum no. 799-1852) can be compared with a floral motif reproduced in the Grammar (‘Indian No.4’, example 17) and with a wallpaper designed by Jones (V&A Museum no. PDP 8336:106). Despite these reservations, at least two of the wallpaper designs by Jones in the V&A collections (figure 17, figure 19) are very similar to motifs illustrated in the Grammar (figure 18, figure 20). In different media, at least two of the silks designed by Jones for Warner in the V&A’s Textiles collections are very close in design to Indian textiles bought from the 1851 Exhibition. Despite Jones’s strictures about copying, ‘Maharanee’ (figure 21) is almost identical to one of the motifs embroidered on a large silk canopy from Multan (figure 22). And, despite its apparently Greek name, the scrolling leaf and flower motifs in Jones’s ‘Athens’ woven satin furnishing fabric for Warner, 1870–74 (figure 23) closely resemble those found in Indian woven silks such as the woven silk and gold-wrapped thread sari (figurev24) and the related example illustrated in the Grammar (figure 25).

Conclusions

While comparisons such as these can become a self-serving exercise, the identification of Owen Jones’s primary source material in the V&A’s Indian textile collections has some value. It provides specific evidence of the high aesthetic esteem placed on Indian artefacts, specifically textiles, by the founders of the Museum and the accompanying nationwide programme of art education. It permits a clearer understanding of the meaning of the principles of good design formed by Jones and his colleagues, and in the case of Jones particularly, how these could be translated into manufactured designs. It also highlights the limitations of translating objects into two-dimensional images, however fine the quality of printing in the case of the Grammar of Ornament. For the textile pieces illustrated were three-dimensional objects, with the texture and (highly-valued) irregularities of the hand-made. Furthermore, most of them were made to be worn, to move with the human body, and to be seen in very different climatic conditions and contexts from those of darkest, gas-lit Victorian England. Seeing these objects next to their ‘mechanical reproduction’ may bring some of these differences into relief.

In terms of the global migration of design motifs, these examples provide a very specific illustration of the way in which traditional patterns of Asian textiles could be mediated through a network of taste arbiters to reach an exhibition in South Kensington, the pages of a ground breaking design manual, and the domestic design productions of nineteenth-century manufacturers of furnishing textiles and wallpaper.

Acknowledgements

This research has been undertaken as part of the V&A/RHULFashioning Diaspora Space research project funded by the AHRC’s Diasporas, Migration and Identities research programme. I am particularly grateful to Rosemary Crill, Senior Curator, V&A South and South-East Asian Collections, for her assistance.

](http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/

“Arts & Humanities Research Council”)

](http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/

“Arts & Humanities Research Council”)

Owen Jones and the V&A Collections

Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament has been an influential design manual for more than 150 years, yet its material sources have not been properly examined. Newly observed connections between the ‘Indian Ornament’ illustrated in the Grammar and textiles in the V&A collections, selected by Jones and his colleagues, may enable better understanding of Jones’s aesthetic principles, and the sources of his own design work.

Endnotes

-

‘The Crystal Palace’. Blackwoods Magazine, September 1, 1854. ↩︎

-

‘Prospects for Schools of Design’. Journal of Design and Manufactures. London, 1849: 89–90. ↩︎

-

Among the exceptions are Darby, Michael. Owen Jones and the Eastern Ideal. PhD Thesis. University of Reading, 1974; Darby M. and D. Van Zanten. ‘Owen Jones’s iron building of the 1850s’. Architectura* (1974): 53–75; Schoeser, Mary. Owen Jones Silks. Warner Fabrics, 1987; Frankel, Nicholas. ‘The Ecstasy of Decoration: The Grammar of Ornament as Embodied Experience’. Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide (Winter 2003): 1–32. Flores, Carol A.H. Owen Jones: design, ornament, architecture, and theory in an age in transition. New York, 2006. In anticipation of Jones’s bicentenary, Journal of Design History has recently published two articles on Jones: Jespersen, John Kresten. ‘Originality and Jones: The Grammar of Ornament of 1856’ 21:2(2008): 143–153, and Sloboda, Stacey. ‘The Grammar of Ornament: Cosmopolitanism and Reform in British Design’ 21:3 (2008): 223–236. None of these texts identify specific sources for the Grammar however. ↩︎

-

The Fashioning Diaspora Space research project being undertaken at the V&A and Royal Holloway University of London, investigates the presence of ‘South Asian’ clothing textiles in ‘British’ culture in both colonial (1850s to 1880s) and post-colonial (1980s to 2000s) times. Research in the V&A is investigating three sets of acquisitions made between 1852 and 1883: purchases from the 1851 Great Exhibition; John Forbes Watson’s Collections of the Textile Manufactures of India (First Series 1866, Second Series 1873–77); and the textiles sent back to South Kensington from India by Caspar Purdon Clarke during his 1881–82 trip to buy objects for the Museum’s Indian collections. ↩︎

-

Snodin, Michael. Introduction to facsimile edition of The Grammar of Ornament by Bernard Quaritch. London, 1997: 8. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: p.x. ↩︎

-

Great Exhibition of the Works of All Nations: Official Catalogue, vol. II, London 1851. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. ‘Lectures on the Results of the Great Exhibition of 1851’. London, 1853. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. ‘Lectures on the Results of the Great Exhibition of 1851’. London, 1853. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: 141. ↩︎

-

From 1791–1858 the East India Company’s India Museum was based at Leadenhall Street; in 1858 the collections were transferred to Whitehall, and in 1879 to the South Kensington Museum. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. ‘Gleanings from the Great Exhibition of 1851’. Reprinted from The Journal of Design (June 1851). ↩︎

-

Wainwright, Clive and Charlotte Gere. ‘The Making of the South Kensington Museum’, parts I & II. Journal of the History of Collections 14:1 (2002): 3–23, 25–44. ↩︎

-

‘The Indian Collection [Disposal and Auction]’. Times, 1 June 1852. ↩︎

-

‘The Indian Collection [Auction]’. Times, 2 July 1852. ↩︎

-

Grammar of Ornament. Proposition 37. ↩︎

-

Robinson, J.C. Catalogue of the Circulating Collection of works of art selected from the museum at South Kensington: intended for temporary exhibitions in provincial schools of art. London, 1860. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: 77. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: 141–2. ↩︎

-

For recent discussion of Jones’s ideas on pattern in relation to design reform and orientalism, see Dutta, Arindam. The Bureaucracy of Beauty: design in the Age of its Global Reproducibility. London, 2008: 116–17, and Sloboda, Stacey. ‘The Grammar of Ornament: Cosmopolitanism and Reform in British Design’. Journal of Design History 21:3 (2008): 223–236. ↩︎

-

Board Minutes … Relative to Acquisition of Art Objects for the benefit of Schools of Art 1852 to 1870 (V&A/AADED 84/34). The price of the Grammar was £17 10s, but was sold in bulk to the Schools of Art at a discounted price of £10 – £12. ↩︎

-

Board Minutes … Relative to Acquisition of Art Objects for the benefit of Schools of Art 1852 to 1870 (V&A/AADED 84/34). ↩︎

-

Raz, Ram. Essay on the Architecture of the Hindus. London, 1834. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: 79. ↩︎

-

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. London, 1856: Preface. ↩︎