There is a longstanding affiliation between confinement and creativity. While restricting the movement of the human form, prisons, workhouses, internment camps, hospitals and asylums have long been the site of great imagination and industry. Nineteenth-century Parisian prisons promoted furniture-making, while in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, British officials in India installed looms in several prisons to produce carpets and textiles.1 In 2010 a V&A exhibition will place examples of over 300 years of British quilting and patchwork within their historical and social contexts. It will include the 1841 ‘Rajah Quilt’, the only known transportation quilt in a public collection, and a newly commissioned collaboration with the charity Fine Cell Work, designed and made by the inmates of HMP Wandsworth.

All of the objects in the exhibition will provide evidence of the ways in which individual makers have responded to their environment, not least in the case of those makers who are working within the unique surroundings of the prison. This paper will focus on the particular work of Elizabeth Fry as a prison reformer in the nineteenth century, her connection to the Rajah Quilt, and offer a consideration of the HMP Wandsworth commission in the light of this history.

Elizabeth Fry and the British prison system

The use of confinement as a punishment for crime is a relatively new concept, and one closely tied to the transportation of convicted felons: a process that started in the eighteenth century and continued for over 200 years.2 The largest movements were to America in the eighteenth century, and then to Australia in the nineteenth century.3 Although the actual punishment was a term of hard labour, many of the earliest prisons were developed as collection points for those awaiting trial or transportation.4 In these early prisons, no distinctions were made between prisoners who might be awaiting trial, debtors, and convicted felons. Furthermore, there was no classification of prisoners based on sex or age.5 Conditions were summarised by the reformer John Howard in ‘The State of the Prisons in England and Wales’ as ‘filthy, corrupt-ridden and unhealthy’.6

Throughout the first three decades of the nineteenth century, Britain witnessed the growth of reformatory theory as a basis for prison discipline, and an increasing interest in rehabilitation initiatives.7 Texts on the subject of prison reform circulated within society, many of which were characterised by both moral fervour and first-hand accounts of prison conditions.8 In particular, the reformer Elizabeth Fry started to stress the humanitarian needs and rehabilitative potential of prisoners, propagating the benefits of social mobility and improvement in the wake of years of punishment and retribution. Fry was born in Norwich on 21 May 1780. She was raised in a Quaker household, and became a minister and preacher for the Society of Friends in 1810. Her interest in prison conditions began after visiting Newgate Prison in 1813 and witnessing the living conditions of women and children.9

Fry’s particular focus was the improvement of conditions for women inmates. Her reform methods involved the establishment of several ladies committees: small groups of women who visited prisons on a regular basis to work directly with inmates, often taking food and clothing with them, but predominantly offering teaching and guidance. In 1821 Fry formed the British Ladies Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners, which formalised the opportunity for women outside the prison to identify with members of their own sex and offer aid and instruction where possible.10 The women of the Ladies Society donated sewing supplies which included tape, ten yards of fabric, four balls of white cotton sewing thread, a ball each of black, red and blue thread, black wool, twenty-four hanks of coloured thread, a thimble, one hundred needles, threads, pins, scissors and two pounds of patchwork pieces (or almost ten metres of fabric).11

Fry’s jurisdiction aimed to replace the primacy of punishment, violence and repression used to regulate social relationships with a pastoral model encouraging education and rehabilitation, affiliation and empathy:12

‘… the female, placed in the prison for her crimes, in the hospital for her sickness, in the asylum for her insanity, or in the workhouse for her poverty, possesses no light or common claim on the pity and attention of those of her own sex, who, through the bounty of a kind Providence, are able to do good.’13

These comments respect a community consciousness shared between women at various levels of society. Fry’s subsequent observations emphasise the importance of providing adequate education and instruction during a period of incarceration, in the understanding that this would lead to a pattern of behaviour desirable during social reintegration. Annemieke van Drenth and Francisca de Haan have suggested that this aspect of Fry’s work can be seen as a secularised variation of the pastoral care developed in the traditions of Christianity and Quakerism.14 Adopting a stricter form of Quakerism in 1799, Fry’s fundamental belief was that divine revelation was immediate and individual, terming such revelation the ‘inward light’ or the ‘inner light’. Fry’s Quakerism rejected a formal creed and stressed inward contemplation as the route to salvation.15 Needlework can be seen as a tool which offered not only a practical skill, but also an enlightened state of contemplation, whereby the focus required for the act of stitching would have allowed the maker to enter a mental space removed from the everyday.

There are numerous objects in public collections that testify to the therapeutic value attached to the needle, but less research has been carried out on the particular choice of patchwork as a tool of reform.16 Fry herself was keen to highlight patchwork as an excellent choice for the women of Newgate:

‘Formerly, patchwork occupied much of the time of the women confined to Newgate, as it still does that of the female convicts on the voyage to New South Wales. It is an exceptional mode of employing the women, if no other work can be procured for them, and is useful as a means for teaching them the art of sewing.’17

Fry draws a subtle distinction here between patchwork and other forms of needlework. While patchwork is useful as an instructional tool (something that the sampler excelled at), it is exceptional in employing and occupying the women. The creation of intricate patchwork required a heavy investment of time. With a lack of active employment, the experience of prison life for many in the early nineteenth century was reduced to the soul-destroying slippage of hours into days. Fry was keen to instil in the prisoner the transformative potential of this experience, turning simply ‘doing time’ into the positive experience of having the time in which to do something, and restoring a sense of control and independence to the inmate.

Integral to the success of Fry’s scheme was attaching value to this time spent: the union of a creative agenda with financial remuneration for the ‘industries’ carried out by the female inmates. These plans were initially resisted:

‘Objections have been made, by some persons, to the employment of prisoners, on the ground that it may be the means of depriving some of the industrious poor of the means of an honest and respectable maintenance.’18

However, Fry sought to persuade prison authorities of the motivational benefits of paid employment.

‘It is to be hoped, however, that such objections will, ere long, cease to be urged; for it is abundantly evident, that unless the time of these poor females, who have abandoned themselves to idleness and vice, be fully occupied while they are in prison, there can be little or no hope that their confinement will lead to their reformation. Without this important aid to prison discipline, their attention will still be directed to the criminal objects which have previously occupied them, and much of their time will probably be spent in contriving plans for future evil. We cannot promote the reformation of such persons more effectively than by making them experimentally acquainted with the fruits of industry … Some remuneration for their work, even during their continuance in confinement, will be found to act as a powerful stimulus to a powerful and persevering industry.’19

Fry’s appeal was successful, and set a precedent for contemporary needlework initiatives.

Fry was not alone in advocating the necessity of financial remuneration for those who took up needlework within the prison. John Francis Maguire was the Mayor of Cork in 1852. In the wake of Ireland’s National Exhibition of the same year, and the successful display of several prison quilts\ he published a text which aimed to highlight ‘the advantages of industrial employment in public institutions, especially those intended for purposes of reformation’.20 In the instance of Cork County Gaol, he notes that:

‘Previous to the year 1847, this gaol was, like others in the country, a place of punishment, rather than of reformation. Despite the zeal of the Governor and the solicitude of the chaplains, it very rarely happened that any unhappy creature out of the many thousands committed to its walls, left its gate improved either in mind or morals.’21

While a ‘select few’ of the prison population were employed in ‘industrial occupation’ (making clothes and carrying out some daily prison duties), it was not until 1847 that a stronger campaign for rehabilitation was put into place:

‘From 1847 up to this year, the inmates have made every article required for their own use, and that of the institution; including male and female clothing of all kinds, in linen and woollen fabrics; bedding, ticken [sic], canvases, blankets, &c … By this alteration in the system of management, every person in the gaol was put to work at some one or other useful employment, instead of being confined, as hitherto, to oakum-picking and stone-breaking, the two grand specifics for the cure of all classes and degrees of public offenders …’22

The result, according to the author, was ‘the good order of the gaol and the improved conduct of its inmates.’23

'The boys are taught, for two hours each day, necessary branches of education, besides receiving an industrial training which, in most cases, they had no opportunity of receiving … And this is the way to reach the object which society should have in view – the reformation of those who it is compelled to punish by its laws; for it is not by degrading a man, that he is to be redeemed and elevated, but by awaking within him whatever good crime or misfortune may have left.24

The emphasis here is on active employment, aimed to improve the inmate’s well-being, social interaction within the prison, and the likelihood of rehabilitation upon release. Maguire highlights the potential of the prison to act as an educational and reformatory institution, propagating a familiarity with the production of goods and the world of trade. The eventual display of the Cork Gaol quilts in the National Exhibition of 1852 implies that Maguire was effective in engaging the inmates with the wider industrial economy (and the associated principles of spectacle, commerce and display), despite their confinement. His terminology of redemption and elevation is also reflective of Fry’s socio-religious discourse, suggesting mental focus as the routes to salvation. These approaches stress the prison as a rehabilitative rather than punitive environment, forwarding the needle as one of the primary tools of utility and reform.

The Rajah quilt

Fry’s extensive accounts and diaries offer an insight into the use of needlework in prisons in the nineteenth century, but today there is relatively little testimony available from the convicts with whom she worked. Often this information is bound up in the objects that the prisoners created. One such object is the only known transportation quilt in a public collection; the Rajah Quilt.

In 1841, patchwork provisions were carried on board the Rajah, to be used by some of the 180 women prisoners on board. The ship left Woolwich on 5th April and arrived in Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (present day Tasmania) on 19th July with 179 women prisoners, and it is thought that up to twenty-nine convict women may have worked the quilt.25

The quilt was acquired in 1989 by the National Gallery of Australia, who believe that it may have been produced under the guidance of Miss Keiza Hayter.26 Hayter had worked at the Millbank Penitentiary, and was given free passage on board in the understanding that she dedicated her time to the improvement of the prisoners. On the recommendation of Fry, Hayter joined the journey to Van Diemen’s Land to assist Lady Franklin in the formation of the Tasmanian Ladies’ Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners.27 The message inscribed on the quilt suggests that Hayter may have continued the educational practices of the Ladies Society,

TO THE LADIES

of the

Convict ship committee.

This quilt worked by the Convicts

of the ship Rajah during their voyage

to van Diemans Land is presented as a

testimony to the gratitude with which

they remember their exertions for their

welfare while in England and during

their passage and also as proof that

they have not neglected the Ladies

kind admonition of being industrious.

June 1841

The quilt suggests a desire to enter into the processes of creation and renewal beyond the instructive space of the prison, while also paying homage to the patronage of the Ladies Committee. The quilt was intended to travel back to Britain as a gift, documenting the safe passage of both the female convicts and Fry’s message to the shores of Van Diemen’s Land. Whether or not Fry saw it before her death is unknown, but it also spoke to a wider audience about the ‘fruits of industry’, claiming the relevance of Fry’s message beyond the walls of Newgate.

The quilt measures 325 × 337 centimetres. It is designed with a central square of Broderie Perse (appliquéd chintz), with twelve frames radiating outwards to form a medallion quilt (a patchwork quilt with a central panel framed by multiple borders).

Broderie Perse coverlets seem to have been particularly popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Two examples are now held by the V&A, and are thought to date from the first half of the nineteenth century. The first (V&A museum no: T.382-1960) is a white cotton coverlet, appliquéd with block-printed chintzes. The central panel contains a peacock, and the frame surrounding this is divided into smaller square compartments containing flowers, Chinese vases and other Chinoiserie motifs (such as birds, trees and small figures in Chinese dress). The outer border of the quilt has a bright red ground printed in black with a classical design of urns, and an eagle and lyre design. Work undertaken at the Museum by Barbara Morris at the time of acquisition dates the textiles, many of which were printed at Bannister Hall near Preston, to between 1804 and 1811. The red and black ‘classical’ border was printed for George Anstey, a leading London linen-draper, in 1804. The Chinese vases come from two fabrics printed at Bannister Hall in 1805 and 1806. Family history undertaken by the donor suggests that the quilt may have been made for an affluent Lancashire family between 1811 and 1815.

The second relevant coverlet in the collection dates from around 1820, and shows a variety of printed cottons appliquéd on a white linen ground (V&A museum no: T.399-1970). The appliquéd prints are mostly flowers, but brightly coloured block printed birds have also been used on the outer border. These fashionable coverlets display the freedom to choose the textiles for the benefit of the design, declaring the household’s access to luxury goods. The Rajah Quilt similarly draws on the popularity of Broderie Perse as a technique, and the desirability of printed cotton chintzes.28 Carolyn Ferguson has undertaken detailed research on the Rajah Quilt for the Quilter’s Guild of the British Isles, and suggests that although it is extremely difficult to say where the fabrics were acquired from, it is likely that the ladies of the Convict Ship Committee would have sourced them from the Manchester merchants operating from warehouses in the Cheapside area of London.29 In particular, Ferguson suggests that the four birds shown on the central panel connect to the printed cottons produced in Manchester, such as those inspired by the prints of John Potts.30 Such printed cottons would have provided a visual reference to the world of trade and commerce, connecting these women to a cross-section of contemporary textile technologies and markets.

It is also important to note that the Rajah Quilt was not a singular example of patchwork created during transportation although, as discussed, it is the only known example in a public collection. As Ferguson notes, a convict on board the ‘Brother’ (1823) sent Fry a calabash as a gift and recorded that she used the patchwork quilt she had made on her bed, while Surgeon Wilson on the Princess Royal reported that many of the women made patchwork quilts and some of them were left behind on the ship.31 Furthermore, in ‘The Fatal Shore’, Robert Hughes describes a court scene enacted by convicts on deck for the purposes of entertainment; ‘cathartic parodies in which the ‘judge’, robed in a patchwork quilt with a swab combed over his head for a wig, his face made up with red-lead, chalk and stove-backing, would volley denunciations at the cowering ‘prisoner’.’32 Hughes also describes the appearance of the great hulls as vast floating ‘street tenements’, with ‘lines of bedding strung out to air between the stumps of the masts’.33 These accounts suggest the presence of patchwork on the visual landscape of the ship, integrated into performances and part of the daily routine of the convict. Each surviving quilt acts as a vessel for its respective narrative, testifying to the convict’s endurance of their journey and the handing down of individual accounts of life at sea.34

The Fine Cell Work commission

The recent Fine Cell Work commission for the V&A engages with this complex history of patchwork produced during confinement. Fine Cell Work is a Registered Charity that teaches needlework to prison inmates. It is based on the vision of Lady Anne Tree, a longstanding prison visitor, entertainments officer at HMP Wandsworth and a prison inspector who continues to support and guide the charity. Fine Cell Work operates through a philanthropic model that reflects Elizabeth Fry’s emphasis on community consciousness. Volunteers work with small groups (of around eleven or twelve) inmates, teaching various needlework skills. Quilting and patchwork skills are taught to all-male groups at HMP Wandsworth. Prisoners involved with the charity carry out their needlework while confined to their cells. Once trained, inmates can be responsible for difficult commissions and support other inmates who are still learning. As one of the inmates enrolled on the scheme points out, one of the benefits of this structure is that it ‘is more consistent and reliable than say education classes because you can do it when you want and in your own time. You can learn from other people.’35 The act of stitching allows the maker to reclaim time as his own. In an environment of finite choices and extensive periods of isolation, this allows the maker to transform hours of confinement into a period of productivity and creativity. At the centre of the Fine Cell Works ethos sits this notion of the individual inmate: the creator, producer and stitcher.

Integral to the success of the charity is the fostering of a sub-culture within the prison that returns to the basic principles of Elizabeth Fry’s reforms: the fruitful relationship between creativity and industry. Prisoners are paid for their work. This ‘generates skills and independence, while also allowing them to save for their release’, hence reducing the likelihood of a return to crime.36 Prisoners often send the money that they earn from Fine Cell Work to their children and families, or use it to pay debts or for accommodation upon release.37 They also develop a skills base that may be useful to them beyond the prison gates. This includes not only the practical aspects of stitching, but also engagement with design initiatives, working to project deadlines and collaborative interaction with the volunteers who instruct them.

The footprint of the V&A commission is based on the Panoptican design of Wandsworth Prison. The quilt will be sewn and designed by inmates across the prison estate, supported by V&A Curator Sue Prichard. The project appears in the wake of several collaborative initiatives between museums and prison charities seeking to reduce the number of inmates who re-offend. In 2006, the Museum of London curated the ‘Mind’s Eye’, featuring twenty-five paintings and fourteen pieces of creative writing by inmates of HMP Wandsworth. Working in collaboration with professional artists and writers, the inmates offered remembrances of London following a series of workshops with artists and writers.38 The exhibition was part of a three-year programme supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund to engage people at risk of social exclusion with their heritage.39

Prior to this, the ‘Black Box’ project (2002–03) involved museums and galleries in East and West Sussex working with prisoners from Ford Prison in Arundel, ‘to create personal museums of the imagination’.40 Participants were invited to take part in a series of workshops led by poets and supported by museum staff and artists. Inspired by artefacts brought in from museum collections, they worked ‘only with images and words’.41 Participants were encouraged to organise and interpret an imaginary space, dividing it into separate ‘rooms’ to house ‘significant, precious and hated things’.42 The project was funded by the MLA South East (Museums, Libraries and Archives), with the aim of engaging ‘hard to reach’ audiences with local collections. The MLA also funded and supported ‘Project Hero’ during the same period, described as ‘creative reader and writer development courses around graphic novels and artefacts for young offenders who were disaffected with education’.43 The Museum of Reading and Reading’s Prison Library worked with young men in the Separated Prisoners Unit at HM Young Offenders Institute, Reading. External evaluation suggests that the pilot project ‘raised the young men’s self esteem and enhanced their key skills in literacy, creativity, communication and social interaction’.44 Since 2003, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has been working with a number of prisons throughout England on the ‘Virtual Egypt’ project.45 Sally-Ann Ashton, a specialist in Egyptology, has been collaborating with prisoners and prison education departments to develop educational resources (in particular, a virtual walk through of the recently refurbished Egyptian galleries). The resulting material will be used for project work in prisons, and also as a public resource. The project combines ‘specialist knowledge with specific cultural experiences to provide learning opportunities and methodologies adapted to those unable to visit museums but of value for much wider application’.46

Furthering the potential of projects that bring together design-led and social rehabilitation initiatives, a recent exhibition entitled ‘The Creative Prison’ explored the ways in which contemporary architecture could offer solutions to current prison conditions.47 The project was developed by architect Will Alsop, artists Shona Illingworth and Jon Ford, and led by the arts organisation Rideout (Creative Arts for Rehabilitation). Collaborating with the staff and inmates of HMP Gartree, Leicestershire, ‘The Creative Prison’ examined how the design of prisons ‘informs their effectiveness and challenges attitudes to current prisoner rehabilitation’.48 The resulting development of an imaginary prison suggested the ways in which architecture could improve safety, interaction and educational activity. It also encouraged prisoners to think proactively about the theme of rehabilitation through film and sculpture.49

In all instances, the emphasis has been on engaging the prisoners with their personal and collective memories, particularly in relation to museum collections, while also increasing their skills base and encouraging a proactive approach to reintegration into the community. The V&A and Fine Cell Work collaboration continues in this vein. The emphasis of the project is on creative expression, personal reflection and community, centred on the act of bringing the participants together to quilt and share their experiences. Recent feedback from stitchers suggests that the resulting acts of communal discourse reinvigorate the prison environment as a site of creative energy. One participant commented on his enjoyment of quilting ‘with so many different people’, recognising that ‘each has their own perspective’.50 For this individual, the act of quilting represents the opportunity to forge links with fellow prisoners:

‘It gives you a purpose to relate to other people. It’s difficult talking to strangers but if you can do it with a reason it helps. You get more sociable because you’re chasing people for materials! … You can learn from other people and teach them something as well. You feel you’ve advanced your knowledge and experience.’51

Large periods of confinement restrict each prisoner’s opportunity to share and attain knowledge and skills, but the co-operative act of creating the quilt engenders a dialogue focused on acts of progression and knowledge.

Each prisoner involved with the commission has the opportunity to design and stitch their own hexagon, which will then be pieced into the larger template of the quilt. Hexagons already completed by prisoners demonstrate a clear conversation with both the history of the British prison system and contemporary discourses on trade and authority. Moving away from the submissive tone and general acceptance present in the inscription of the Rajah Quilt, the HMP Wandsworth Quilt offers a critical engagement with the system in which the prisoner is encased. The following design displays the longstanding association between labour and prison life.

The overbearing hand of authority (Figure 1) dominates the physical landscape, overtly referencing the hard and monotonous prison tasks of marching and rock-breaking promoted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as punishing/suitableforms of employment for prisoners.

In placing the hand in plain view, the stitcher also encourages a contemplation of the absolute importance of the hand in the life of the prisoner (both metaphorically in the hand of authority, and literally as the tool of salvation for the stitcher). Many of the hexagons return us to the image of the hand or the physical impression left by it.

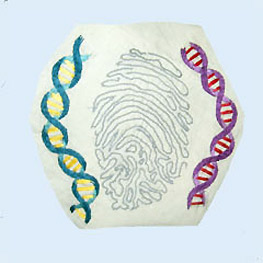

Here (fig. 2), a fingerprint is surrounded by borders of DNA, references the heightened interest in the scientific identification of the criminal (through fingerprinting and recent developments in forensics). It also suggests wider discourses on personal freedom, and government initiatives to introduce tighter forms of identification.

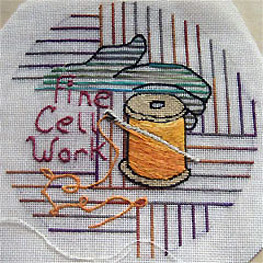

Other hexagons (fig. 3) engage directly with the action of the probation board, and return us to the process of stitching by bringing the needle and thread to the foreground to present the tools of the maker.

The diversity of these designs demonstrates the continuing appeal of the needle as a tool of both subversion and salvation, and the critical dialogue initiated by the prisoners challenges current attitudes to prison life.

Many reflect on the ongoing presence of punitive measures in the face of growing external and internal pressures on the prison system, including steadily increasing numbers of inmates (and serious overcrowding) and constraints in public expenditure.52

Within this environment, the enduring appeal of the needle as a tool of salvation is a claim supported by documents from prison inmates working with Fine Cell:

I’m a life-serving prisoner and for years I have been trying to escape. I have tried numerous cell hobbies which promptly ended up discarded in the corner of the cell as so much rubbish. Due to depression, most of the time I’ve been unwashed, unshaven, teeth not cleaned, hair not combed, as often as not my cell has been dirty and stinking. I’ve had no possessions, nobody to love me, just hanging onto a futile, empty and miserable existence.

Every night I’ve asked God to have mercy on me and not to make me endure another day. I’ve wept and I asked why I was in this world, I am good for nothing, no money, no family and with no-one I could go to for help. I just couldn’t understand why I should go on living. Then something happened to me.

I was lying in my cell one evening when a bloke came in and asked if I can help him. I didn’t know the fella, but he had helped me with cigarette papers and teabags. He explained how he’d broken his glasses and needed to finish a pattern he was sewing for the in-cell charity course. Although I class myself as being very butch and sewing so very feminine, I figured I owed him, so I agreed to help him finish his work. He showed me what it was I had to do, I made him promise not to tell anybody and I hid it in a cupboard in my cell. About nine o’clock I got it out and started sewing. Before I knew where I was they started unlocking us for breakfast, a whole night had come and gone with no thoughts of suicide, and no tears of melancholy.

How good it is to be alive, to feel that I am accomplishing something and my life has real meaning. Nobody really enjoys an aimless life, a life without purpose, do they? Around the world millions of people are working hard and trying to find happiness in living.’53

For this individual who perceives himself emotionally and physically trapped, the needle offers focus and purpose, and the possibility of mental ‘escape’ from the monotony of prison life. Initially ashamed of engaging in what he perceives as gendered work, the prisoner develops a strong sense of fulfilment and achievement based on the act of stitching.

Many of the Fine Cell Work stitchers acknowledge not only the reassuring rhythmic repetition of the act of sewing, but also the cultural meaning attached to the objects that they produce. There is often a great poignancy for participants in offering up their own time and designs for public consumption, and the realisation that something important to them is appreciated by the rest of society. A prisoner’s comment that ‘we’re like a forgotten community’ acknowledges the shared experiences of those within the prison walls, but also the strong sense of alienation that comes into being when entering or leaving the prison gates.54 For this reason, the Fine Cell Work participants sew in the knowledge that the HMP Wandsworth Quilt will be on view in a public exhibition in 2010, striking a connection between the exhibition audience and the prisoners who helped to create it. As part of the permanent collections at the V&A, it will also form a lasting legacy for these men, tying together personal memories to form a collective document of prison life as it stands in 2010.

In dialogue with the Rajah Quilt, it is hoped that the HMP Wandsworth Quilt will encourage an understanding of quilts as part of a hybrid history of creative practice. The HMP Wandsworth Quilt both resonates with the complexity of this history, remembering the skills and experiences of past prisoners, and explores the continuing relevance of the prison as a site of creativity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sue Prichard at the V&A and Katy Emck at Fine Cell Work for their knowledge and support with this paper.

Endnotes

-

For example in Paris in 1834, female and male wood gilders struck the patron of a furniture shop who had contracted prison labour. ‘Gazette des tribunaux’, no. 2734 (23 May 1834), cited by DeGroat, Judith A. ‘The Public Nature of Women’s Work: Definitions and Debates during the Revolution of 1848’. French Historical Studies 20: 1 (Winter, 1997): 35. A report from 1913 on the prison system in India suggests that in Poona ‘the industries are varied. Men were weaving a fine rug, the director chanting the indications of the pattern from a manuscript, while the weavers responded antiphonally and placed the threads, and so the figures grew to the rhythm of music’. See Henderson, Charles Richmond. ‘Control of Crime in India’. Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 4: 3 (September, 1913): 387 and 394. ↩︎

-

For an overview of how our ideas of punishment have changed over time see Norval Morris and D.J. Rothman, The Oxford History of the Prison: the Practice of Punishment in Western Society (Oxford, 1995). ↩︎

-

Between 1718 and 1775 around 30,000 convicts were transported to the West Indies and North America for periods of between seven and fourteen years. From 1787, around 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia over a period of 80 years. See Nick Flynn and Douglas Hurd, Introduction to Prisons and Imprisonment (London, 1998), pp.29–30. ↩︎

-

When transportation to the American colonies was interrupted in 1776 by the American War of Independence, old sailing ships known as ‘hulks’ had to be brought into use on the Thames. In 1779 an Act introduced a new concept of hard labour for prisoners in the hulks, commencing with dredging the river Thames, and made provision for the building of two penitentiaries. There was considerable delay in building these institutions. Transportation to Australia became possible in 1787, thus relieving the pressure on the hulks, so it was not until 1816 that construction of convict prisons commenced. Hulks continued to be used until 1859 and at one time contained 70,000 prisoners, many being French prisoners of war captured after the defeat of Napoleon. See Amy Edwards, ‘Home Office: 1782–1982’ (London, 1982), p.2. Document available via HM Prison Service Website. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

John Howard, ‘The State of the Prisons’ (1777). ↩︎

-

Evidence exists of the particular relevance of commercially-orientated needlework to these initiatives. In the Great Exhibition catalogue of 1851, several examples of quilts and needlework were displayed by the inmates of Richmond Lunatic Asylum, and further examples by the Royal Victoria Asylum for the Blind. See The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue in Three Volumes, Vol. 2 (London, 1851), pp.569 and 570. Richmond Lunatic Asylum also displayed quilts at Ireland’s ‘National Exhibition of 1852’, along with the Dublin District Lunatic Asylum, Richmond Female Penitentiary and Cork County Gaol. See John Francis Maguire, The Industrial Movement in Ireland, as Illustrated by the National Exhibition of 1852 (Dublin, 1853), p.258. ↩︎

-

The reformatory view of prisons between 1815 and 1835 was in the large part characterised by the zeal of religious societies. For example, the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline and the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders was active during this time, and its committee included well known Quakers and members of the Church of England such as Joseph Fry, William Allen, Samuel Guerney, Thomas Hancock, Samuel Hoare, Thomas Foxwell Buxton, Lord Suffield, William Crawford, Johnand Walter Venning and Francis Cunningham. For a further account see William James Forsythe, The Reform of Prisoners 1830–1900 (London, 1987), p.17. ↩︎

-

Thomas Timpson gives the following account of Elizabeth Fry’s initial impressions: ‘The part of the prison allotted to them was a scene of the wildest disorder. Swearing, drinking, gambling, and fighting, were their only employments; filth and corruption prevailed on every side.’ See Thomas Timpson, Memoirs of Mrs Elizabeth Fry: including a history of her labours in promoting the reformation of female prisoners, and the improvement of British seamen (New York, 1847), p.29. ↩︎

-

Peter Gordon and David Doughan, A Dictionary of British Women’s Organisations: 1825–1960 (London, 2005), p.29. ↩︎

-

Robert Bell, ‘The Rajah Quilt’. ↩︎

-

Such practices in prison work originated amongst wider social reform movements, such as calls for the abolition of slavery. See Annemieke van Drenth and Francisca de Haan, The Rise of Caring Power: Elizabeth Fry and Josephine Butler in Britain and the Netherlands (Amsterdam, 1999), p.169. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Fry, Observations on the Visiting, Superintending, and Government, of Female Prisoners (Norwich, 1827), p.7. ↩︎

-

Annemieke van Drenth and Francisca de Haan, The Rise of Caring Power: Elizabeth Fry and Josephine Butler in Britain and the Netherlands (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999). ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

For example, the V&A holds a sampler stitched by Elizabeth Parker. The sampler tells the story of its maker in red stitches on a neutral ground. She describes her family, the violence and ‘cruelty’ that she encounters when she enters into service at the age of thirteen, and her thoughts on taking her own life. The narrative ends ambiguously, with Elizabeth contemplating ‘what will become of my soul’. For further information on the sampler see Maureen Daly Goggin, ‘One English Woman’s Story in Silken Ink: filling in the missing strands in Elizabeth Parkers circa 1830 sampler’, ‘Sampler and Antique Needlework Quarterly’ vol.29 (Winter 2002). ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Fry, Observations on the Visiting, Superintending, and Government, of Female Prisoners (Norwich, 1827), p.51. ↩︎

-

Ibid, p.49. ↩︎

-

Ibid, pp.49–52. ↩︎

-

John Francis Maguire, The Industrial Movement in Ireland, as Illustrated by the National Exhibition of 1852 (Dublin, 1853), p.258. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. pp.259–60. ↩︎

-

Ibid. p.260. ↩︎

-

Ibid. pp.260–61. ↩︎

-

Information from the Australian National Quilt Register. Further information is held at the National Gallery of Australia on the Rajah’s voyage and the women transported to Australia. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Robert Bell, ‘The Rajah Quilt’. ↩︎

-

In the case of some of the square patches, tiny pieces of chintz have been pieced together to give the appearance of complete squares, or supplemented with plainer cottons. ↩︎

-

Carolyn Ferguson, ‘A Study of Quakers, Convicts and Quilts’ in ‘Quilt Studies’ 8 (2007), pp.54–5. ↩︎

-

Ibid. There is also a subtext to the quilt in that the fashionable textiles and broderie perse design clearly connect with a strand of society for whom travel and exploration widened access to luxury goods, while for the makers of the Rajah quilt, journeying across the globe brought with it a huge amount of trepidation. ↩︎

-

Carolyn Ferguson, ‘A Study of Quakers, Convicts and Quilts’, Quilt Studies 8 (2007), p.45. ↩︎

-

Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore (London: 2003), p.154. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p.138. ↩︎

-

The later examples of the Changi quilts, created by women in the internment camps after the surrender of Singapore to Japanese troops in 1942, affirm the close affiliation between quilting and systems of communication. Although these women were prisoners of war rather than convicts, each patch communicates the survival of a woman, her endurance, her time passed, and her refusal to disappear from the visual landscape. One of these quilts is now held by the British Red Cross Museum in London. See http://www.redcross.org.uk/. ↩︎

-

Annette Holland and Rebecca Price, Fine Cell Work Newsletter (London, 2006). ↩︎

-

Ibid. Government statistics suggest that six out of ten prisoners reoffend with two years of their release, and economic pressures are often cited as one of the main reasons. Recent policy documents such as ‘Reducing Re-offending Through Skills and Employment’ (2005) and ‘Reducing Re-Offending Through Skills and Employment: Next Steps’ (2006) set out how education and learning can contribute to this goal. These documents are accessible via the Ministry of Justice’s ‘Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills’ website (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Annette Holland and Rebecca Price, Fine Cell Work Newsletter (London, 2006). ↩︎

-

For further information on the exhibition see http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/English/EventsExhibitions/Past (cited 2008). Liza Ramrayka offers an analysis of the exhibition and its relation to reform initiatives, and suggests its high success rate. Of the 15 inmates who started the project, 11 completed the course. The weekly attendance rate was 86%, and 50% of those who completed an evaluation for the Museum of London said that they had acquired useful knowledge or skills ‘to a high extent’, while the same proportion said they had done so ‘to a good extent’. See Liza Ramrayka, ‘Unlocking potential’, Museums Journal 39 (November 2006), pp.38–41. ↩︎

-

Liza Ramrayka, ‘Unlocking potential’, Museums Journal 39 (November 2006), p.38. ↩︎

-

http://www.mlasoutheast.org.uk/whatwedo/equality/hardtoreachaudiences/ (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

http://www.mlasoutheast.org.uk/whatwedo/equality/hardtoreachaudiences/ (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Liza Ramrayka, ‘Unlocking potential’, Museums Journal 39 (November 2006), p.39. ↩︎

-

http://www.mlasoutheast.org.uk/whatwedo/equality/hardtoreachaudiences/ (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Further details on the project are available via http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/dept/ant/egypt/virtual/ (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

The exhibition ran at the Architecture Foundation’s Yard Gallery, from 19 January to 16 February 2007. See http://www.architecturefoundation.org.uk (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

http://www.architecturefoundation.org.uk (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Conversation between Fine Cell Works and an anonymous contributor to the HMP Wandsworth Quilt, transcribed by Katy Emck. In an email to the author, 28 August 2008. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Amy Edwards, Home Office: 1782–1982 (London, 1982), p.7. Document available via HM Prison Service Website (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Anonymous, ‘Letter from a Prisoner’ http://www.finecellwork.co.uk/ix/letters_article/go(LETTER_FROM_PRISONER_PAGE) (cited 2008) ↩︎

-

Conversation between Fine Cell Works and an anonymous contributor to the HMP Wandsworth Quilt, transcribed by Katy Emck. In an email to the author, 28 August 2008. ↩︎